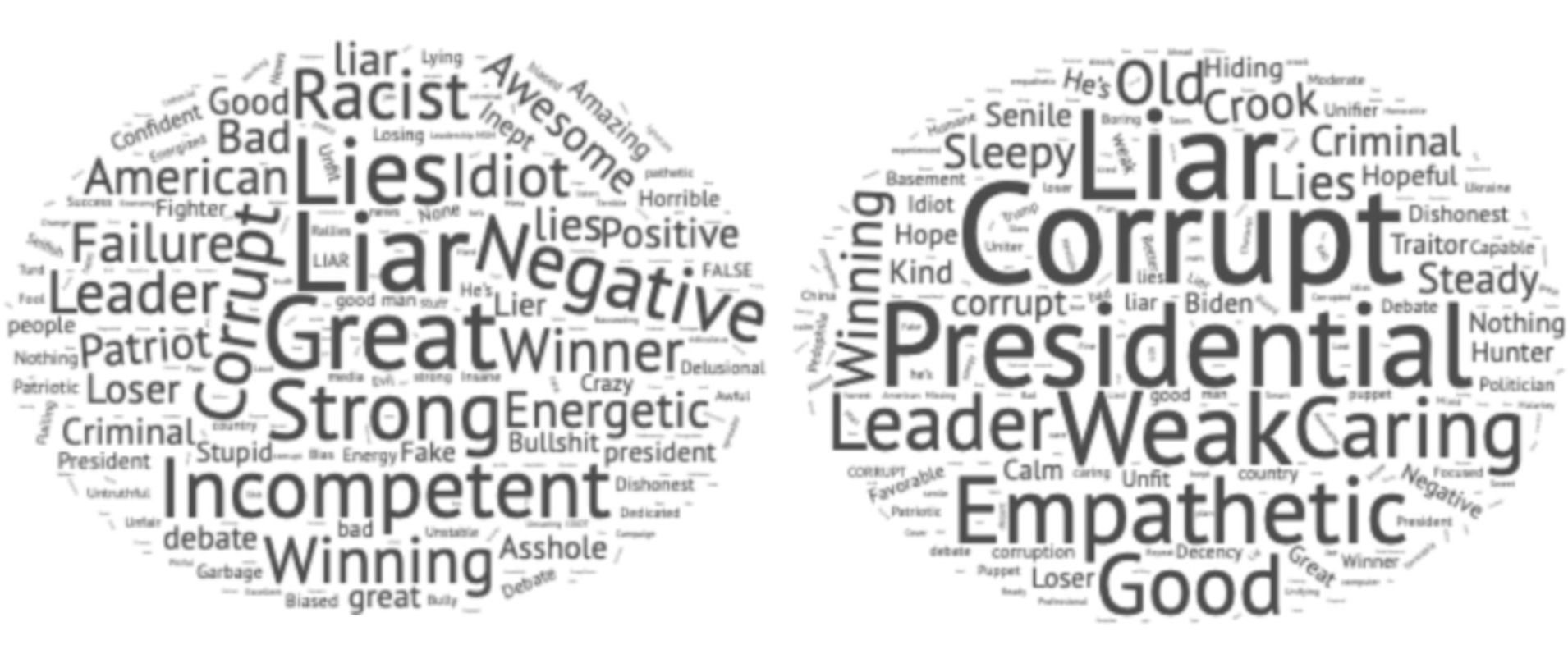

As the 2016 election entered the home stretch, the polling firm Gallup produced a visual representation of what voters had heard about both Hillary Clinton and Donald Trump. The resulting word clouds have stood for four years as a perfect distillation of political media failures that allowed an incompetent con artist and bigot to become president of the United States.

In the absence of professional habits that would’ve allowed them to convey the true stakes of the election—that Trump was a unique threat to the republic, while Clinton was a flawed but committed public servant with a concrete agenda—journalists chased what political operators wanted them to. And what Trump—the loudest, and most attention-seeking operator—wanted them to cover was Hillary Clinton’s emails.

The effect was to detach public perception from reality and invert the two.

Given the narrowness of Trump’s victory, and with the benefit of a full-term’s hindsight, it’s reasonable to stipulate that more responsible, faithful coverage of the 2016 campaign would have spared the country immense misery and the degradation of the rule of law.

For years, legacy media has agonized over its role in the outcome of the election without ever fully acknowledging it, or fully correcting the problems that fueled it. And so for years, critics have wondered with a nagging sense of dread whether the campaign press corps would do the same thing all over again in 2020, and steer the country past its only offramp along the road to kleptocracy.

Or would it do better?

We now have an answer to that latter question, and the answer is—thankfully, imperfectly—yes. The unanswered question is whether the journalists and outlets that comprise the press corps will view these improvements as a one-time-only departure from habit, or whether better habits will stick.

For the final entry in our PollerCoaster 2020 partnership with Change Research, we generated our own word clouds to help us gauge what has broken through to voters and what hasn’t. The comparison isn’t perfect. These are snapshots of a much different moment in time, one that happens to be consumed by a once-a-century pandemic, where Trump is the incumbent, not the challenger. But just as Gallup did, we asked likely voters to provide one-word responses “to describe what you’ve heard” about the candidates in the past week. And though the results don’t come close to perfectly capturing the essences of Trump and Joe Biden, or their relative merits, the improvement from four years ago is remarkable.

This comes, of course, despite the right’s best efforts.

Since the early days of the Democratic primary, Republicans have been trying to manufacture scandal around Biden, the best-polling of Trump’s potential 2020 opponents, with the goal of costing him the presidential nomination or crippling his general-election candidacy.

Trump quickly commingled election scheming and agitprop with his governing powers, as he extorted and bribed foreign governments to dirty up his rival, and got himself impeached for it. But even in these, the waning days of the campaign, GOP operatives remain committed, desperate even, to guilt trip, bully, and otherwise pressure the media to treat anti-Biden propaganda with the same credulousness that turned BENGHAZI and, thus, ultimately EMAILS into catchwords. They want our Biden word cloud to scream HUNTER or BURISMA, and recognize their failure to pull it off has likely dealt a fatal blow to Trump’s re-election hopes

💯. If you can watch this and say this Biden story isn’t worth covering you’re a political operative not a journalist. https://t.co/y21gbZEDZC

— Josh Holmes (@HolmesJosh) October 28, 2020

Still, they accomplished a lot. The fact that “Liar” and “Lies” loom almost as large in Biden’s word cloud as in Trump’s, and that the word “Corrupt” squats dead center in Biden’s, yet lurks almost invisibly in Trump’s, is a product of something. Democratic political failures and smaller-scale media failures likely explain some of it. Despite her many strengths as a moderator, NBC’s Kristen Welker asked one question about nepotism at the final presidential debate, and somehow didn’t direct it at the candidate whose children work at the White House while simultaneously helping run his business empire.

But none of it would be possible without the powerful propaganda machine the right has spent decades building. Even against the backdrop of a deadly pandemic that, due to Trump’s lies and incompetence, has killed hundreds of thousands of Americans, the right has managed to create a miasma of scandal around Biden out of almost nothing, and turn it into one of a handful of core campaign issues.

The Biden allegations Republicans have spun up are extremely convoluted. But their Benghazi conspiracy theories were also convoluted. The email-server scandal was simpler but it became hopelessly intertwined with the unrelated theft and leaking of Democratic Party emails, which revealed no unethical conduct, but, through roadblock media coverage, drove a hazy sense that something malfeasant lay at the bottom of it all. What truly made the difference between 2016 and 2020 is that the mainstream press hasn’t served as a gleeful validator of right-wing spin and smears and conspiracy theories this time. Without facts on their side, the right can still elevate a fabricated scandal into the middle-tier of public consciousness, but without buy-in from the mainstream press, it will stay there—which is why our word clouds look so different from Gallup’s.

But the propaganda machine won’t stop whirring after the election, even if Trump loses. And so the unanswered question I asked above—will journalists view these improvements as a one-time-only concession, or will they stick?—may soon become the most important one in politics.

New York Times media columnist Ben Smith recently cast the relative professionalism with which political reporters treated the Biden smears as vindication for professional journalists. He argued further that the way they’ve covered the campaign represents a “reassert[ion]” of gatekeepers, who for a time found themselves overwhelmed by forces like Trump and social media and foreign disinformation that they weren’t immediately equipped to grapple with.

It’s a hopeful interpretation, but I’m not so confident that, having risen adequately to one challenge, journalists won’t quickly resume letting Fox and other purveyors of propaganda lead them around by the nose. After publishing his column, Smith himself briefly amplified misleading information about the Biden imbroglio from an untrustworthy source, before providing fuller context from his own newspaper.

In an email to me, Smith drew a distinction between the published work of a newspaper and the thinking-out-loud that all politicos do on Twitter, where words and ideas are more fleeting. “I think mainstream media institutions have the ability, more than they think they did, to impose proportion and context—that’s the thing twitter lacks most,” he wrote. “I don’t think my tweet was equivalent to a column in the paper, or a front page article, say. I also think…it’s possible to have a modulated conversation about news on social media and that doing so isn’t equivalent to a screaming headline.”

This is a real and important distinction, but it’s one that becomes increasingly difficult to draw around the musings of reporters who have hundreds of thousands or millions of social media followers. In either case, though, the episode underscores the point that to remain steeled against bad-faith actors will require constant vigilance and the changing of old mores governing how journalists treat sources of information.

If Biden wins, we’ll learn almost right away whether the lessons of 2016 and 2020 have stuck or not. Republicans and their right-wing media allies may set aside their failed Hunter Biden fixation, but they’ll move on to other things: insincere and baseless scaremongering about federal debt, pretending to value political norms and the importance of congressional oversight, a sudden discovery that elections don’t have consequences after all, even when the winner has a popular mandate. No one can stop conservatives from doing what they believe to be in their political interests, but the test of whether the gatekeepers have reasserted themselves will be whether or not they revert to pretending to believe the same old propaganda. Whether they view their resistance to one such campaign as a major, one-off achievement rather than what it should be: a basic obligation of the trade. Whether the next word cloud looks more like ours, or the one that prefigured the past four years of hell.