Paul Ryan’s decision to retire from the House of Representatives at the end of this term has been depicted by his admirers as akin to a prizefighter going out on a high note. Less than five months ago, President Trump signed into law Ryan’s most significant legislative achievement, the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017 (TCJA), capping off a 20 year career in Congress, and allowing him to retire with what Rep. Kevin Brady (R-TX) called “Reagan-like achievements” under his belt.

However, analysis conducted by Data for Progress based on polls of both the Speaker’s ideas and his personal popularity belie this rosy narrative. The data reveal a stark truth: Ryan’s platform has almost never been less popular than it is now. Though the tax cut bill represents the more palatable half of Ryan’s agenda, it is still unpopular, and required Ryan to align himself with Donald Trump, at enormous cost to his carefully crafted, but undeserved reputation as an earnest wonk. In so doing, he also ensured that the future of the GOP belonged to Trump and an administration more concerned with cultural grievances than gutting the welfare state. Instead of laying the foundation for an age of fiscal conservatism, the tax bill more likely represents the last gasp of a failed trickle-down ideology.

Paul Ryan and the Decline of Austerity

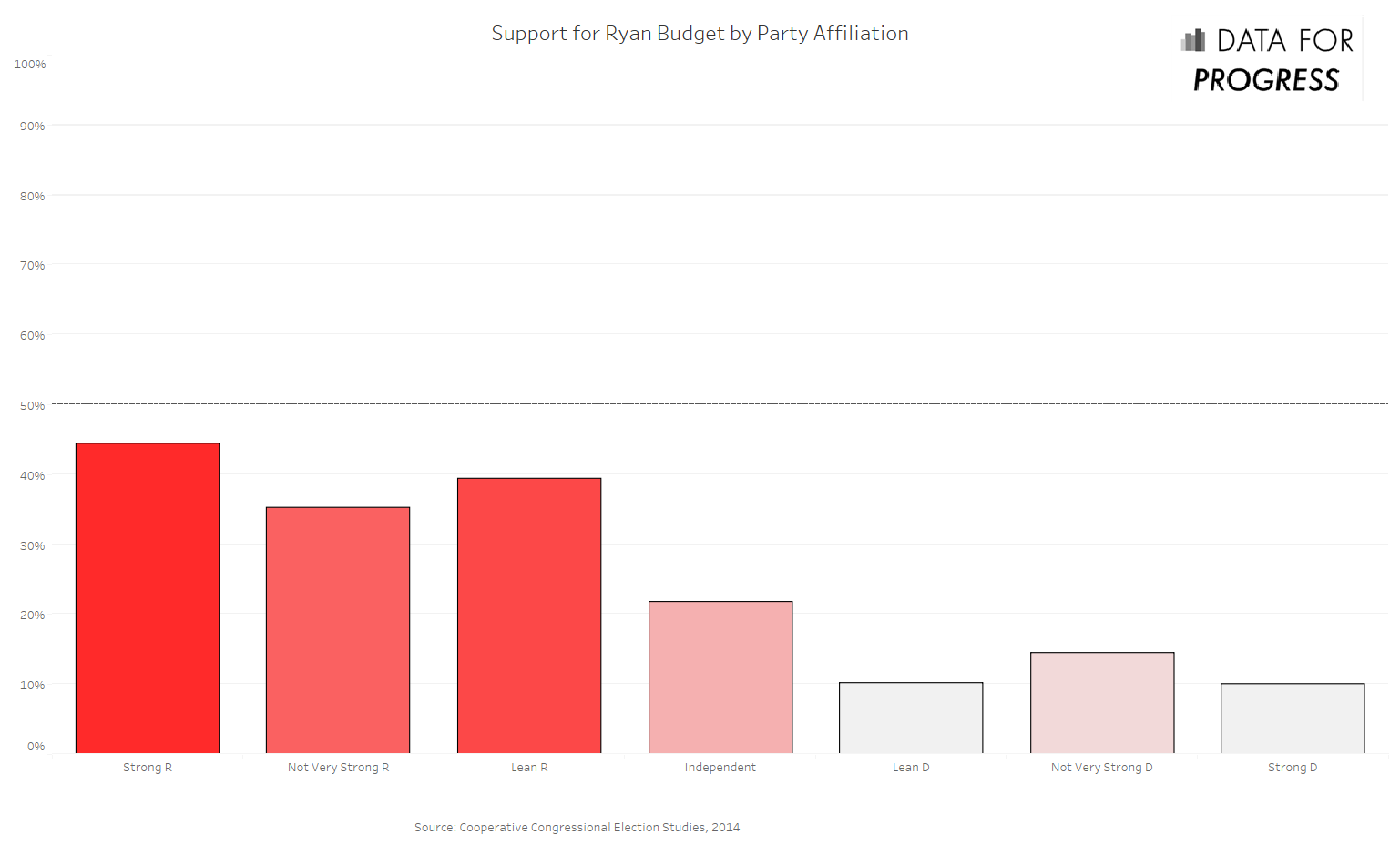

Paul Ryan’s agenda has never been broadly popular with the American public—even in the wake of the 2012 election, when Republicans ran on Ryan’s agenda and placed him, as their vice presidential nominee, at the top of the ticket. In the 2014 Cooperative Congressional Election Survey, respondents were asked whether they would support or oppose the Ryan Budget, described to them as legislation that would “would cut Medicare and Medicaid by 42 percent. Would reduce debt by 16 percent by 2020.” Only 24 percent of the general public supported Ryan’s budget.

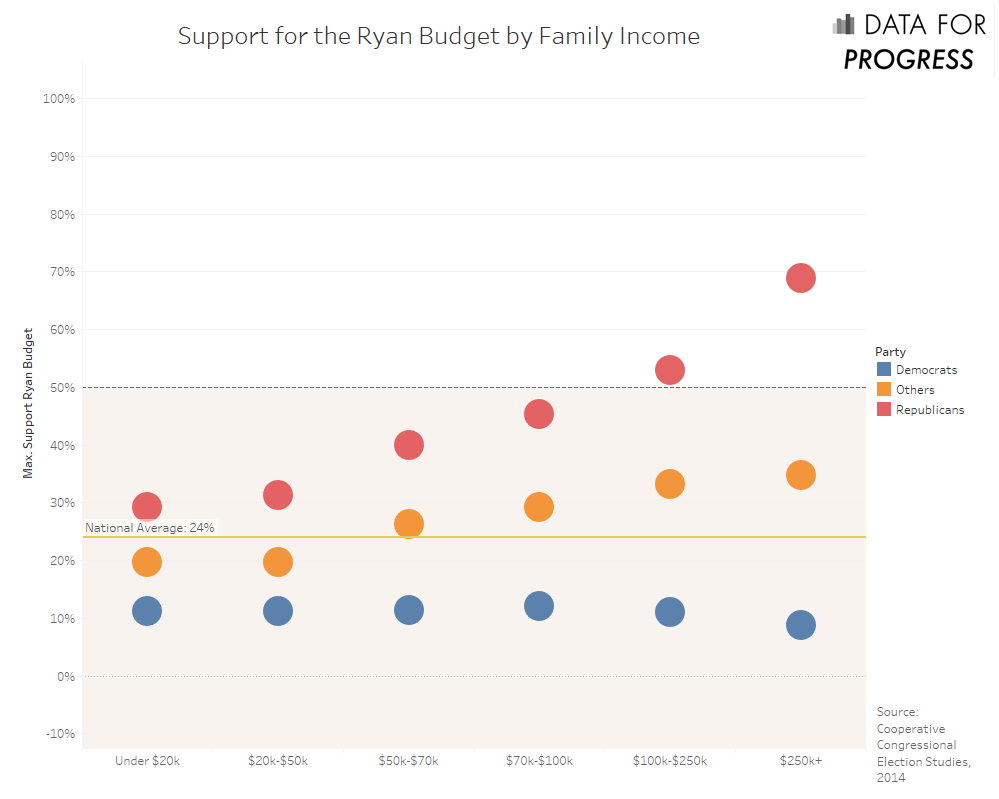

His budget had less than 50 percent popular support with every political affiliation, even people who listed themselves as “Strong Republicans.” Ryan’s budget was popular with a particular subset of Republicans, specifically those making above $80,000 per year, tracking upward with wealth, until reaching 68 percent with GOP voters making more than $250k.

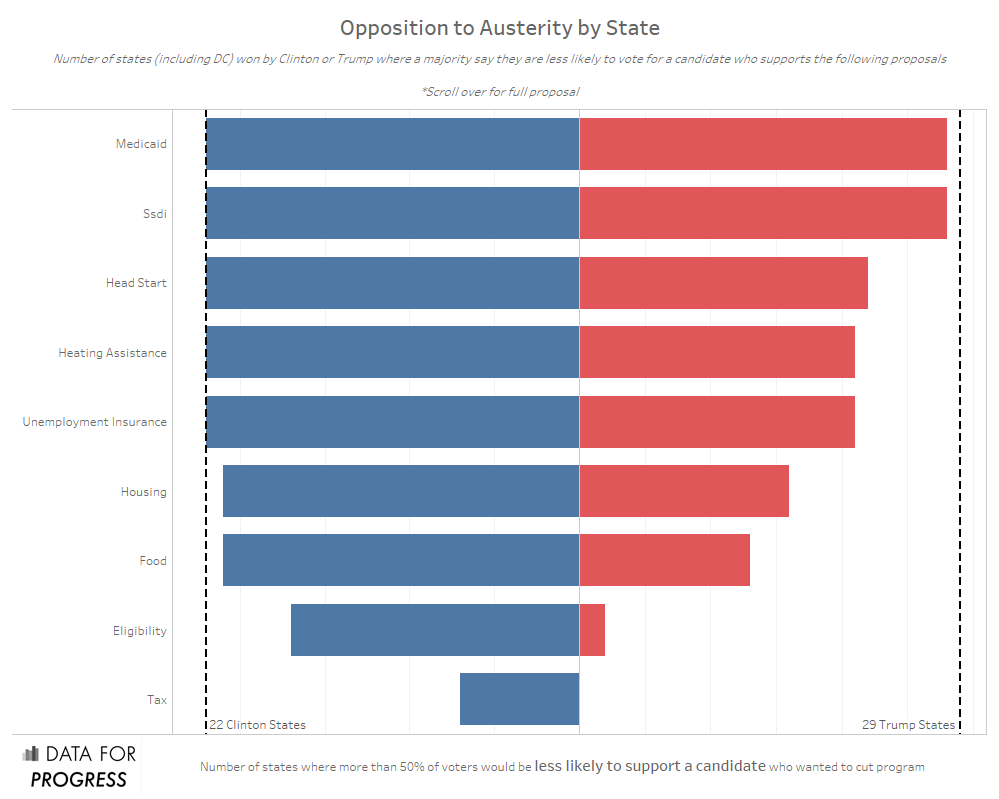

Given this low baseline and isolated support, we should expect any candidate who openly runs on the Ryan agenda to have difficulty winning elections. Data for Progress estimated how people in specific states felt about Ryan-style austerity using a technique called Multilevel Regression and Post-stratification (MRP). The data we analyzed comes from a Center for American Progress poll conducted in January of 2018 asking respondents whether a candidate’s support for various policy positions would change the likelihood of the respondent voting for that candidate1. The policies polled included the Republican Party’s tax cut (TCJA), generic questions about cuts to the social safety net, and inquiries about cuts to specific federal programs. While opposition to the generic social safety net cuts and Ryan’s tax bill tended to be stronger in blue states, cuts to specific programs yielded broad opposition.

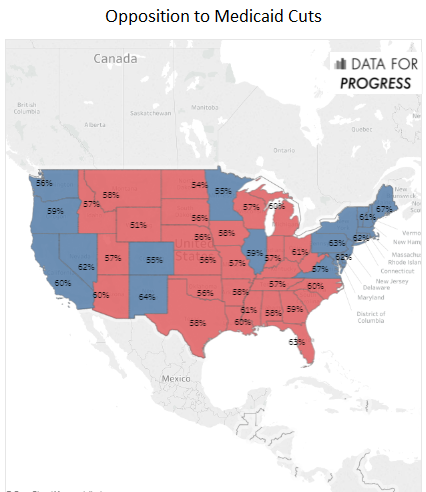

Based on this data, we estimate that majorities in both Clinton and Trump states are averse to cutting critical social spending programs. In 22 out of the 22 states (including the District of Columbia) that voted for Clinton, and 28 out of the 29 states that voted for Trump, majorities would be disinclined to vote for candidates who want to cut Medicaid or Social Security Disability Insurance (SSDI). Furthermore, in all states that voted for Clinton, majorities said they would be less likely to vote for candidates who support cutting Unemployment Insurance (UI), heating assistance, and Head Start, and in all but one state that voted for Clinton a majority of voters said the same about Food Stamps and housing programs. Similarly, in over 20 of the 29 states that went to Trump, majorities said they would be less likely to vote for a candidate supporting cuts to UI, heating assistance, and Head Start.

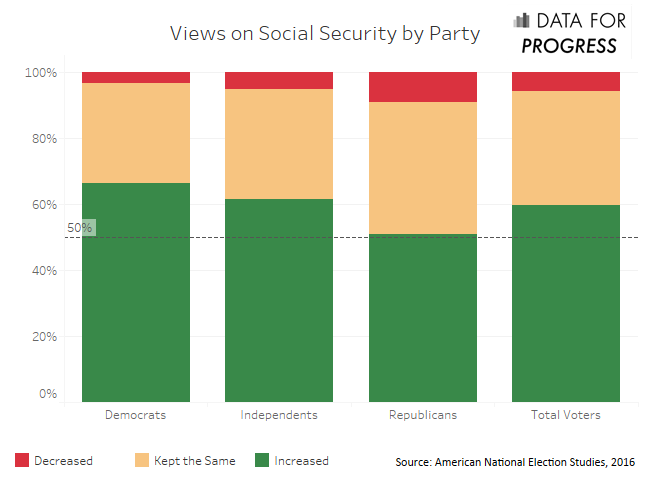

Our analysis is substantiated by recent national polls on the specifics of the Ryan agenda. Ryan’s budget proposals have always entailed draconian cuts to the country’s largest entitlement programs and a rash of national surveys since the election suggest these proposals remain deeply unpopular. According to the American National Election Study, only about six percent of the public thinks that Social Security should be cut, an order of magnitude less than the 60 percent who say it should be expanded.

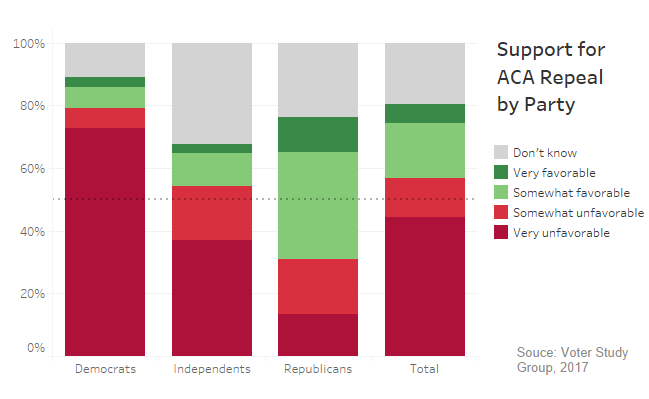

Cuts to other programs are deeply unpopular as well. According to a 2017 poll by the Voter Study Group only 24 percent of the public favors repealing Obamacare and its dramatic expansion of Medicaid. Even among Republicans, only 11 percent strongly favor repeal, whereas 18 percent are strongly opposed to doing so.

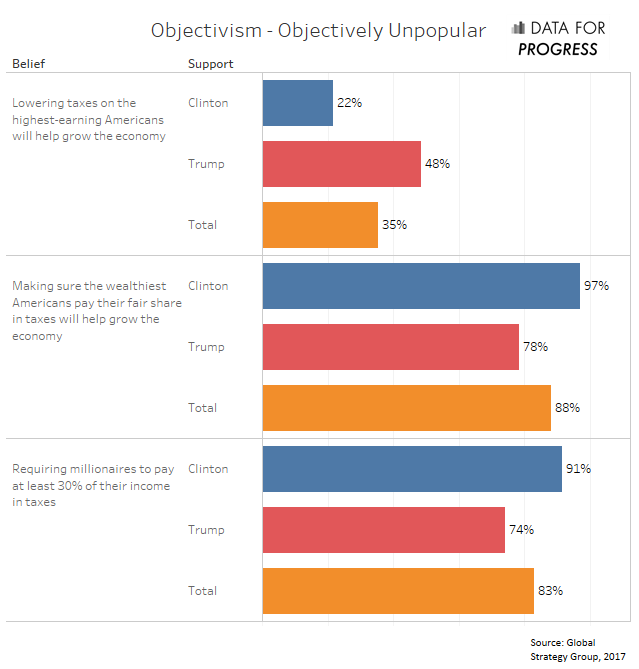

This almost unique level of bipartisan disdain is rooted in a deeper rejection of the core philosophies underpinning Ryan’s worldview. This can be seen in polling by Global Strategy Group commissioned by Not One Penny:

- 22 percent of Clinton voters and 48 percent of Trump voters agree that, “lowering taxes on the highest-earning Americans will help grow the economy.”

- 97 percent of Clinton voters and 78 percent of Trump voters agree that “making sure the wealthiest Americans pay their fair share in taxes will help grow the economy.”

- 91 percent of Clinton voters and 74 percent of Trump voters support the Buffet Rule, requiring people who earn more than one million dollars per year to pay at least 30 percent of their income in federal taxes. Ryan cut taxes for wealthy people dramatically, despite the fact that voters already thought the rich paid too little.

It’s Trump’s Party Now

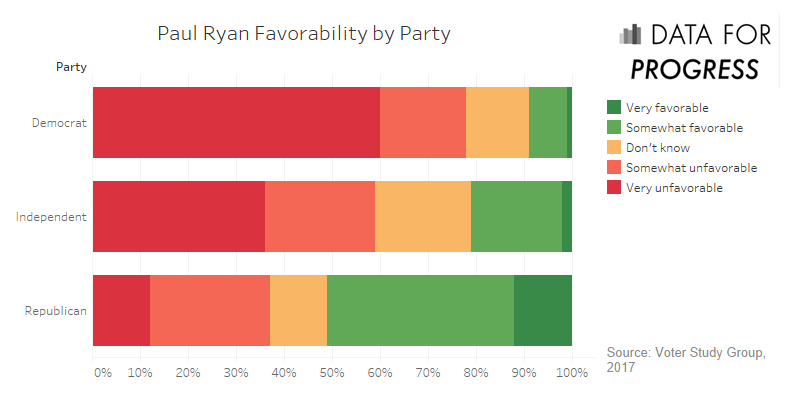

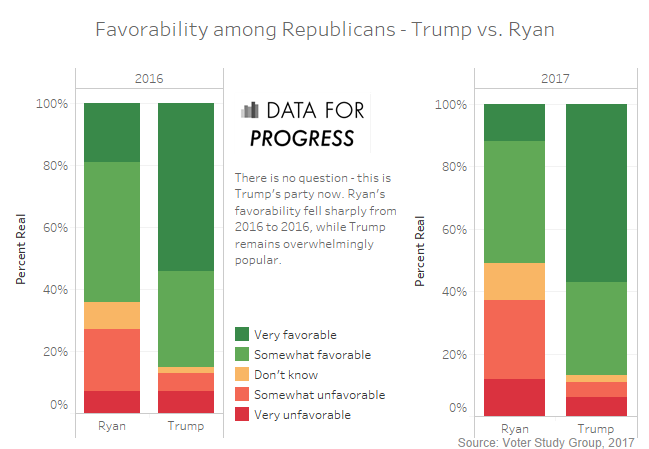

Given this rejection of austerity and Ryan’s close association with it, it should come as little surprise that he has lost standing with the Republican base, necessitating an alliance with Donald Trump. Ryan leaves Congress with a five percent very favorable rating and a 21 percent somewhat favorable rating—numbers dwarfed by the 38 percent of Americans who have a very unfavorable opinion of Ryan and the 21 percent who view him somewhat unfavorably. Only 12 percent of Republicans have very favorable views of him, roughly the same share as Republicans who have a very unfavorable view of him.

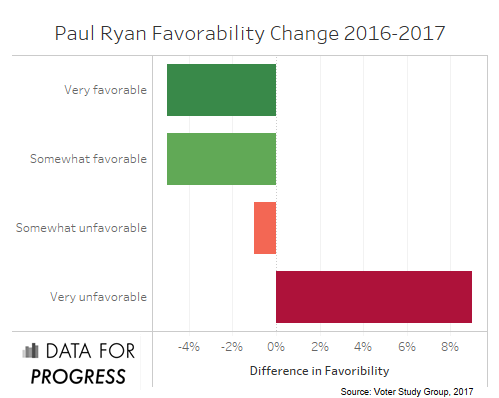

Just as notable is the fact that he has become more unpopular as his party assumed power and issues took center stage. Between 2016 and 2017, Ryan’s very unfavorable rating increased nine percent, and was accompanied by a reciprocal five percent decline in both his very favorable and somewhat favorable numbers .

At a time Ryan is becoming more and more unpopular, Trump enjoys broad support from the Republican base. Between 2016 and 2017, Donald Trump’s very favorable rating among Republicans increased by three points (from 54 percent to 57 percent) while Ryan’s fell from 19 percent to 12 percent. Ryan’s very unfavorable rating increased from seven percent to 12 percent, while Trump’s fell slightly. The Republicans haven’t just come home to Trump, they’ve done so while leaving Ryan behind.

The Case for Optimism

No liberal will celebrate the decline of Ryanism if it means the rise of Trumpism. But wider context offers hope. The data suggests that modern progressive policies are widely popular nationwide. Even with Ryan’s retirement, the progressive agenda still faces strong headwinds in the form of voter suppression and other undemocratic forces–many championed by Ryan himself. The challenge of overcoming these forces is compounded by insurgent nativist and racist sentiments powered by Donald Trump. But the fact remains that Paul Ryan has always been fighting political gravity, and in achieving his greatest policy win, he has ensured his own irrelevance.

Sean McElwee is a co-founder of Data for Progress. He tweets at @SeanMcElwee.

Avery Wendell is a data scientist based in San Francisco and senior adviser to Data for Progress. He tweets at @awendell98.

Colin McAuliffe is a New Jersey based activist and data scientist and a co-founder of Data for Progress. He tweets at @ColinJMcAuliffe.

Jason Ganz is a data analyst based in Denver and senior adviser to Data for Progress. He tweets at @jasnonaz.

1 It is certainly the case that self-reported changes in the likelihood of voting for a candidate conditional on policy positions should not be taken purely at face value. A strong partisan may feel that there is no issue position that would meaningfully change their likelihood of voting for a particular candidate, while a weakly committed voter may express changes in their vote intention on all manner of issues that, at the end of the day, won’t affect their eventual vote choice. We prefer to interpret responses to these questions as indications of general affect. When a respondent says they’d be less likely to vote for a politician who supported a given policy, that’s a good indication that, at the very least, they have negative views of that policy—which is what we’re really after here anyway.